What Contributions Has Romare Bearden Made in the Field of Art?

| Romare Bearden | |

|---|---|

Romare Bearden, in his regular army uniform, a photo taken by Carl Van Vechten, 1944 | |

| Born | Romare Howard Bearden (1911-09-02)September 2, 1911 Charlotte, Northward Carolina, Usa |

| Died | March 12, 1988(1988-03-12) (anile 76) New York City, US |

| Known for | Painting |

Romare Bearden (September two, 1911 – March 12, 1988) was an African-American creative person, author, and songwriter. He worked with many types of media including cartoons, oils, and collages. Born in Charlotte, Due north Carolina, Bearden grew upwardly in New York City and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and graduated from New York Academy in 1935.

He began his artistic career creating scenes of the American South. Subsequently, he worked to express the humanity he felt was lacking in the world after his experience in the Usa Army during Globe War II on the European forepart. He returned to Paris in 1950 and studied fine art history and philosophy at the Sorbonne.

Bearden's early piece of work focused on unity and cooperation within the African-American community. After a period during the 1950s when he painted more abstractly, this theme reemerged in his collage works of the 1960s. The New York Times described Bearden equally "the nation's foremost collagist" in his 1988 obituary.[1] Bearden became a founding member of the Harlem-based fine art grouping known as The Screw, formed to discuss the responsibility of the African-American artist in the civil rights movement.

Bearden was the author or coauthor of several books. He likewise was a songwriter, known as co-writer of the jazz classic "Body of water Breeze", which was recorded by Billy Eckstine, a former high school classmate at Peabody High School, and Dizzy Gillespie. He had long supported young, emerging artists, and he and his married woman established the Bearden Foundation to proceed this work, as well as to support young scholars. In 1987, Bearden was awarded the National Medal of Arts.

Teaching [edit]

Bearden was built-in in Charlotte, North Carolina. Bearden's family moved with him to New York City when he was a toddler, as role of the Great Migration. Later on enrolling in P.Southward. 5 in 1917, on 141 Street and Edgecombe Avenue in Harlem, Bearden attended P.S. 139, followed by DeWitt Clinton High Schoolhouse.[2] In 1927 he moved to Eastward Liberty, Pittsburgh,[three] with his grandparents,[four] [2] then returned to New York City. The Bearden household soon became a meeting place for major figures of the Harlem Renaissance.[five] His father, Howard Bearden, was a pianist.[6] Romare's mother, Bessye Bearden, played an active role with the New York Urban center Board of Instruction, and too served as founder and president of the Colored Women's Autonomous League. She was also a New York contributor for The Chicago Defender, an African-American newspaper.[7]

In 1929, he graduated from Peabody High School in Pittsburgh. He enrolled in Lincoln Academy, the nation'south second oldest historically blackness college, founded in 1854. He later transferred to Boston University where he served as art managing director for Beanpot, Boston Academy'southward student humour magazine.[viii] Bearden continued his studies at New York Academy (NYU), where he started to focus more on his fine art and less on athletics, and became a atomic number 82 cartoonist and art editor for The Medley, the monthly periodical of the secretive Eucleian Society at NYU.[nine] Bearden studied fine art, education, science, and mathematics, graduating with a degree in science and pedagogy in 1935.

He continued his creative study under German artist George Grosz at the Fine art Students League in 1936 and 1937. During this period Bearden supported himself by working as a political cartoonist for African-American newspapers, including the Baltimore Afro-American, where he published a weekly cartoon from 1935 until 1937.[10]

Semi-professional baseball career [edit]

As a child, Bearden played baseball in empty lots in his neighborhood.[xi] He enjoyed sports, throwing discus for his high school runway team and trying out for football.[12] Later on his mother became the New York editor for the Chicago Defender, he did some writing for the paper, including some stories about baseball. Only in one case Bearden transferred from Lincoln University to Boston University, he became the starting fullback for the schoolhouse football team (1931-two) and then began pitching - first for the freshman team and eventually for the school's varsity baseball game team.[4] [xiii] He was awarded a document of merit for his pitching at BU, which he hung with pride in subsequent homes throughout his life.[14]

While at Boston University he played for the Boston Tigers, a semi-professional person, all Black team based in the neighborhood of Roxbury. He tended to play with them during the BU baseball off-flavour and had opportunities to play both iconic Negro League and white baseball game teams. For example, he pitched against Satchel Paige while playing for the Pittsburg Crawfords for a summer,[xv] and played exhibition games against teams such every bit the House of David and the Kansas Urban center Monarchs.[14] When Philadelphia Athletics catcher, Mickey Cochraine, brought a number of teammates to play a game against BU, Bearden gave upwards only i hit—impressing Athletics owner Connie Mack.[xiv] Mack offered Bearden a place on the Athletics 15 years earlier Jackie Robinson became the first Black role player in major league baseball. Sources conflict about whether Mack idea Bearden was white[4] or told Bearden he would have to pass for white.[16] [17] Despite the Athletics World Series in 1929 and 1930, and the American League pennant in 1931,[18] Bearden decided he did not desire to hide his identity and chose not to play for the Athletics.[17] After two summers with the Boston Tigers, an injury made Bearden rethink the attention he was giving to baseball and he put greater focus into his art, instead.[12]

Career every bit an creative person [edit]

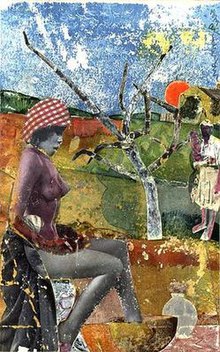

Patchwork Quilt, cut-and-pasted material and paper with constructed polymer pigment on composition board, 1970, Museum of Modern Art

Bearden grew as an artist past exploring his life experiences. His early on paintings were often of scenes in the American Southward, and his manner was strongly influenced past the Mexican muralists, especially Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco. In 1935, Bearden became a case worker for the Harlem function of the New York City Section of Social Services.[vii] Throughout his career as an artist, Bearden worked as a case worker off and on to supplement his income.[7] During World War Two, Bearden joined the United States Army, serving from 1942 until 1945, largely in Europe.[19]

Later serving in the ground forces, Bearden joined the Samuel Kootz Gallery, a commercial gallery in New York that featured avant-garde fine art. He produced paintings at this time in "an expressionistic, linear, semi-abstract way."[7] He returned to Europe in 1950 to study philosophy with Gaston Bachelard and fine art history at the Sorbonne, under the auspices of the Grand.I. Neb.[7] [19] Bearden traveled throughout Europe, visiting Picasso and other artists.[7]

Making major changes in his art, he started producing abstruse representations of what he deemed every bit homo, specifically scenes from the Passion of Jesus. He had evolved from what Edward Alden Jewell, a reviewer for the New York Times, called a "debilitating focus on Regionalist and ethnic concerns" to what became known every bit his stylistic approach, which participated in the post-war aims of avant-garde American art.[20] His works were exhibited at the Samuel M. Kootz gallery until it was deemed not abstract enough.

During Bearden'southward success in the gallery, notwithstanding, he produced Golgotha, a painting from his series of the Passion of Jesus (see Figure 1). Golgotha is an abstract representation of the Crucifixion. The middle of the viewer is drawn to the middle of the epitome first, where Bearden has rendered Christ's body. The body parts are stylized into abstruse geometric shapes, yet are still too realistic to be concretely abstract; this work has a experience of early Cubism. The body is in a central position and darkly contrasted with the highlighted crowds. The crowds of people are on the left and correct, and are encapsulated inside big spheres of bright colors of purple and indigo. The background of the painting is depicted in lighter jewel tones dissected with linear black ink. Bearden used these colors and contrasts because of the abstract influence of the time, just besides for their meanings.

Bearden (right) discussing his painting Cotton fiber Workers with Pvt. Charles H. Alston, his offset art teacher and cousin, in 1944. Both Bearden and Alston were members of the 372nd Infantry Regiment stationed in New York City.

Bearden wanted to explore the emotions and deportment of the crowds gathered effectually the Crucifixion. He worked difficult to "depict myths in an attempt to convey universal human being values and reactions."[21] According to Bearden, Christ's life, expiry, and resurrection are the greatest expressions of human'southward humanism, considering of the idea of him that lived on through other men. Information technology is why Bearden focuses on Christ's body outset, to portray the idea of the myth, then highlights the oversupply, to testify how the idea is passed on to men.

Bearden was focusing on the spiritual intent. He wanted to show ideas of humanism and thought that cannot be seen by the eye, but "must be digested by the mind".[22] This is in accordance with his times, during which other noted artists created abstract representations of historically significant events, such equally Robert Motherwell'south celebration of the Castilian Civil War, Jackson Pollock's investigation of Northwest Coast Indian fine art, Mark Rothko's and Barnett Newman's interpretations of Biblical stories, etc. Bearden depicted humanity through abstract expressionism after feeling he did not run across it during the state of war.[9] Bearden's work was less abstract than these other artists, and Sam Kootz's gallery ended its representation of him.

Bearden turned to music, co-writing the hitting song "Sea Cakewalk", which was recorded by Baton Eckstine and Dizzy Gillespie. It is still considered a jazz archetype.[23]

In 1954, at age 42, Bearden married Nanette Rohan, a 27-yr-old dancer from Staten Island, New York.[24] She later on became an artist and critic. The couple somewhen created the Bearden Foundation to assist young artists.

In the tardily 1950s, Bearden'southward work became more than abstract. He used layers of oil paint to produce muted, hidden effects. In 1956, Bearden began studying with a Chinese calligrapher, whom he credits with introducing him to new ideas most infinite and composition which he used in painting. He also spent much time studying famous European paintings he admired, particularly the work of the Dutch artists Johannes Vermeer, Pieter de Hooch, and Rembrandt. He began exhibiting once more in 1960. About this time he and his married woman established a second home on the Caribbean isle of St. Maarten. In 1961, Bearden joined the Cordier and Ekstrom Gallery in New York Metropolis, which would represent him for the rest of his career.[seven]

In the early 1960s in Harlem, Bearden was a founding member of the art group known as The Spiral, formed "for the purpose of discussing the delivery of the Negro creative person in the present struggle for civil liberties, and as a discussion group to consider mutual aesthetic issues."[25] The first meeting was held in Bearden's studio on July 5, 1963, and was attended by Bearden, Unhurt Woodruff, Charles Alston, Norman Lewis, James Yeargans, Felrath Hines, Richard Mayhew, and William Pritchard. Woodruff was responsible for naming the group The Screw, suggesting the mode in which the Archimedean spiral ascends upward as a symbol of progress. Over fourth dimension the group expanded to include Merton Simpson, Emma Amos, Reginald Gammon, Alvin Hollingsworth, Calvin Douglas, Perry Ferguson, William Majors and Earle Miller. Stylistically the grouping ranged from Abstract Expressionists to social protest painters.[25]

Bearden's collage work began in 1963 or 1964.[seven] He first combined images cut from magazines and colored paper, which he would often further alter with the utilise of sandpaper, bleach, graphite or paint.[7] Bearden enlarged these collages through the photostat process.[7] Building on the momentum from a successful exhibition of his photostat pieces at the Cordier and Ekstrom Gallery in 1964, Bearden was invited to practise a solo exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. This heightened his public contour.[7] Bearden's collage techniques changed over the years, and in later on pieces he would apply blown-upward photostat photographic images, silk-screens, colored paper, and billboard pieces to create big collages on sheet and fiberboard.[vii]

In 1971, the Museum of Modern Fine art held a retrospective exhibition of Bearden'south work,[7] which traveled to the University Art Museum in Berkeley, California. The Urban center of Berkeley then commissioned Bearden to create a mural for the Metropolis Quango chambers. The xvi-foot-broad landscape, incorporating many visual aspects of the urban center in collage style, was installed in tardily 1973 and received positive reviews.[26] It was taken down and loaned to a National Gallery of Art Bearden retrospective in 2003 that traveled to the San Francisco Museum of Modernistic Art, the Dallas Museum of Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art.[27] Following that tour it has been in storage while the City Hall edifice has awaited a seismic retrofit and the urban center quango has been coming together elsewhere. A portion of the mural inspired the city's current logo.[28]

Early on works [edit]

His early on works advise the importance of African Americans' unity and cooperation. For instance, The Visitation implies the importance of collaboration of black communities by depicting intimacy betwixt two black women who are holding hands. Bearden'south vernacular realism represented in the piece of work makes The Visitation noteworthy; he describes two figures in The Visitation somewhat realistically but does not fully follow pure realism, and distorts and exaggerates some parts of their bodies to "convey an experiential feeling or subjective disposition."[29] Bearden said, "the Negro artists [...] must not be content with merely recording a scene as a machine. He must enter wholeheartedly into the situation he wishes to convey."[29]

In 1942, Bearden produced Factory Workers (gouache on casein on brown kraft paper mounted on board), which was commissioned by Forbes magazine to accompany an article titled The Negro's War.[30] The article "examined the social and financial costs of racial discrimination during wartime and advocated for full integration of the American workplace."[31] Factory Workers and its companion piece Folk Musicians serve every bit prime examples of the influence that Mexican muralists played in Bearden's early work.[30] [31]

Collage [edit]

Bearden had struggled with 2 artistic sides of himself: his background every bit "a student of literature and of artistic traditions, and beingness a blackness homo beingness involves very existent experiences, figurative and concrete,"[32] which was at combat with the mid-twentieth century "exploration of abstraction".[33] His frustration with brainchild won over, every bit he himself described his paintings' focus as coming to a plateau. Bearden then turned to a completely different medium at a very important time for the country.

During the civil rights movement, Bearden started to experiment over again, this time with forms of collage.[34] After helping to found an artists group in support of civil rights, Bearden expressed representational and more overtly socially witting aspects in his work. He used clippings from magazines, which in and of itself was a new medium, every bit glossy magazines were fairly new. He used these glossy scraps to contain modernity in his works, trying to testify how African-American rights were moving forward, and so was his socially conscious fine art. In 1964, he held an exhibition he called Projections, where he introduced his new collage style. These works were very well received and are mostly considered to be his best work.[35]

Bearden had numerous museum shows of his piece of work since then, including a 1971 show at the Museum of Modernistic Art entitled Prevalence of Ritual, an exhibition of his prints, entitled A Graphic Odyssey showing the work of the terminal fifteen years of his life;[36] and the 2005 National Gallery of Art retrospective entitled The Art of Romare Bearden. In 2011, Michael Rosenfeld Gallery exhibited its 2d bear witness of the artist's work, Romare Bearden (1911–1988): Collage, A Centennial Celebration, an intimate group of 21 collages produced between 1964 and 1983.[37]

One of his most famous series, Prevalence of Ritual, concentrates mostly on southern African-American life. He used these collages to show his rejection of the Harmon Foundation's (a New York Urban center arts system) emphasis on the idea that African Americans must reproduce their culture in their fine art.[38] Bearden found this approach to be a burden on African artists, because he saw the idea every bit creating an accent on reproduction of something that already exists in the earth. He used this new series to speak out against this limitation on Black artists, and to emphasize modern art.

In this series, one of the pieces is entitled Baptism. Bearden was influenced past Francisco de Zurbarán, and based Baptism on Zurbarán's painting The Virgin Protectress of the Carthusians. Bearden wanted to prove how the water that is about to be poured on the subject area being baptized is always moving, giving the whole collage a experience and sense of temporal flux. He wanted to express how African Americans' rights were always changing, and order itself was in a temporal flux at the time. Bearden wanted to show that nada is fixed, and expressed this thought throughout the image: non simply is the subject almost to take water poured from the top, but the subject is also to be submerged in h2o. Every aspect of the collage is moving and will never exist the aforementioned more than than in one case, which was congruent with order at the fourth dimension.

In "The Fine art of Romare Bearden", Ruth Fine describes his themes as "universal". "A well-read man whose friends were other artists, writers, poets and jazz musicians, Bearden mined their worlds also as his ain for topics to explore. He took his imagery from both the everyday rituals of African American rural life in the south and urban life in the northward, melding those American experiences with his personal experiences and with the themes of classical literature, religion, myth, music and daily human ritual."[ citation needed ]

In 2008 a 1984 landscape by Romare Bearden in the Gateway Center subway station in Pittsburgh was estimated as worth $15 meg, more than the cash-strapped transit agency expected. It raised questions about how it should be cared for once it is removed before the station is demolished.[39]

"We did not expect information technology to exist that much," Port Authority of Allegheny Canton spokeswoman Judi McNeil said. "We don't have the wherewithal to be a caretaker of such a valuable piece." Information technology would cost the agency more than $100,000 a year to insure the threescore-by-13-foot (18.3 by four.0 1000) tile landscape, McNeil said. Bearden was paid $xc,000 for the project, titled Pittsburgh Recollections. Information technology was installed in 1984.[39]

Before his death, Bearden claimed the collage fragments aided him to conductor the past into the present: "When I conjure these memories, they are of the present to me, because after all, the creative person is a kind of enchanter in time."[xl]

The Render of Odysseus, one of his collage works held by the Art Constitute of Chicago, exemplifies Bearden'due south attempt to represent African-American rights in a grade of collage. This collage describes one of the scenes in Homer'due south epic Odyssey, in which the hero Odysseus is returning home from his long journey. The viewer's eye is first captured by the main figure, Odysseus, situated at the heart of the work and reaching his hand to his wife. All the figures are blackness, enlarging the context of the Greek legend. This is one of the ways in which Bearden works to represent African-American rights; by replacing white characters with blacks, he attempts to defeat the rigidity of historical roles and stereotypes and open upwards the possibilities and potential of blacks. "Bearden may have seen Odysseus as a stiff mental model for the African-American community, which had endured its own adversities and setbacks."[41] By portraying Odysseus every bit black, Bearden maximizes the potential for empathy by black audiences.

Bearden said that he used collage because "he felt that art portraying the lives of African Americans did not give full value to the individual. [...] In doing so he was able to combine abstruse fine art with existent images so that people of dissimilar cultures could grasp the field of study matter of the African American culture: The people. This is why his theme ever exemplified people of color."[42] In improver, he said that collage's technique of gathering several pieces together to create i assembled work "symbolizes the coming together of tradition and communities."[41]

Music [edit]

In addition to painting, collage, and athletics, Bearden enjoyed music and even composed a number of songs.

In 1960, Loften Mitchell released the iii act play, Star of the Forenoon, for which he wrote the script and music, and Bearden and Clyde Pull a fast one on wrote the lyrics.[43] [44]

A selection of them tin be heard on the 2003 album Romare Bearden Revealed, created by the Branford Marsalis Quartet.[45] [46]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "I'chiliad Slappin' Seventh Avenue" (Duke Ellington/Irving Mills/Henry Nemo) | 2:01 |

| 2. | "Jungle Blues" (Jelly Curlicue Morton) | eight:48 |

| 3. | "Seabreeze" (Fred Norman/Larry Douglas/Romare Bearden) | half-dozen:13 |

| 4. | "J Mood" (Wynton Marsalis) | x:48 |

| 5. | "B's Paris Blues" (Branford Marsalis) | 4:27 |

| 6. | "Fall Lamp" (Doug Wamble) | 2:52 |

| vii. | "Steppin' on the Blues" (Lovie Austin/Jimmy O'Bryant/Tommy Ladnier) | 4:53 |

| 8. | "Laughin' and Talkin' with Higg" (Jeff "Tain" Watts) | ten:40 |

| 9. | "Carolina Shout" (James P. Johnson) | 2:35 |

Legacy [edit]

Romare Bearden died in New York City on March 12, 1988, due to complications from bone cancer. The New York Times described Bearden in its obituary equally "one of America'south pre-eminent artists" and "the nation's foremost collagist."[one]

Ii years after his death, the Romare Bearden Foundation was founded. This non-profit arrangement not merely serves as Bearden'south official estate, but too helps "to preserve and perpetuate the legacy of this preeminent American artist."[47] Recently, it has begun developing grant-giving programs aimed at funding and supporting children, immature (emerging) artists, and scholars.[48]

In Charlotte, a street was named after Bearden, intersecting West Boulevard, on the west side of the metropolis. Romare Bearden Bulldoze is lined by the West Boulevard Public Library and rows of townhouses.

Within the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Main Library (310 N. Tryon Street) is Bearden'southward mosaic, Earlier Dawn.[49] Later Bearden's decease, his widow selected a 12-by-18-inch (300 mm × 460 mm) collage by him to be recreated in smalti (glass tiles) by Crovatto Mosaics in Spilimbergo, Italy, for the grand reopening gala (June xviii, 1989) of the "new" library. She was publicly honored at the ceremony for her contribution. The reinterpreted piece of work is 9 anxiety (ii.seven m) tall and 13.5 feet (four.one m) wide.

Footing breaking for Romare Bearden Park in Charlotte took place on September 2, 2011, and the completed park opened in late Baronial 2013. Information technology is situated on a 5.2-acre (2.ane ha) parcel located in Third Ward between Church and Mint streets. The artist lived virtually the new park for a time as a child, at the corner of what is now MLK Boulevard and Graham Street. The park design is based on piece of work of public artist Norie Sato.[50] Her concepts were inspired by Bearden's multimedia collages. Fittingly, the park serves every bit an entryway to a pocket-sized league baseball game stadium, BB&T Charlotte Knights Ballpark.[51]

DC Moore Gallery currently represents the estate of Romare Bearden. The beginning exhibition of his works at the gallery was in September 2008.[52] In 2014-15, Columbia University hosted a major Smithsonian Institution travelling exhibition of Bearden's work and an accompanying series of lectures, readings, performances, and other events celebrating the creative person. On brandish at the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Gallery on Columbia'due south Morningside campus, and also at Columbia'south Global Centers in Paris and Istanbul, Romare Bearden: A Black Odyssey focused on the bicycle of collages and watercolors Bearden completed in 1977 based on Homer's epic poem, The Odyssey.[53]

In 2011, the U.S. Mail released a set of Forever stamps featuring four of Bearden'due south paintings during a first-day-of-issuance ceremony at the Schomburg Eye for Research in Black Civilization.[54]

In 2017, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond appear acquisition of Romare Bearden's collage, 3 Folk Musicians, as part of the museum's permanent collection. The collage, which shows two guitar players and a banjo actor, is often cited in art history books. Information technology was shown at the VMFA for the kickoff time in Feb 2017 in the museum's mid- to belatedly 20th-century galleries.[55]

Published works [edit]

Romare Bearden is the author of:

- Lil Dan, the Drummer Boy, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003

Romare Bearden is the coauthor of:

- with Harry Henderson, Vi Black Masters of American Fine art, New York: Doubleday, 1972[19]

- with Carl Holty, The Painter's Mind, Taylor & Francis, originally published in 1969[xix]

- with Harry Henderson, of A History of African-American Artists. From 1792 to The Present, New York: Pantheon Books 1993[19]

Honors achieved [edit]

- Founded the 306 Group, a club for Harlem artists

- In 1966 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- In 1972 he was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Messages

- In 1978, Bearden was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Acquaintance member

- In 1987, the year before he died, he was awarded the National Medal of Arts

- In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Romare Bearden on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[56]

Awards [edit]

- American Academy of Arts and Letters Painting Award, 1966[19]

- National Plant of Arts and Letters grant, 1966[19]

- Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship, 1970[nineteen]

- Ford Foundation Fellowship, 1973[19]

- Medal of the State of North Carolina, 1976[nineteen]

- Frederick Douglas Medal, New York Urban League, 1978[19]

- James Weldon Johnson Award, Atlanta Chapter of NAACP, 1978[19]

Works of art [edit]

- Abstruse (painting)

- The Blues (collage) – 1975, Honolulu Museum of Art

- The Calabash (collage) – 1970, Library of Congress

- Carolina Shout (collage) This is eponymous with the musical composition by Bearden family friend, the "dean of jazz pianists" and composer, James P. Johnson. This appears to exist more a coincidence, equally the proper name of Bearden's mother, Bessye (sic), is listed on the letterhead of an organization chosen, " Friends of James P. Johnson" An sound recording of Carolina Shout, featuring Harry Connick Jr. on pianoforte, is included on the companion CD to the National Gallery of Art Exhibition, Romare Bearden Revealed, by Branford Marsalis. – The Mint Museum of Art

- The Dove

- Falling star (painting)

- Fisherman (painting)

- "Jammin' at the Savoy" (painting)

- The Lantern (painting)

- Final of the Blue Devils

- Madonna and Kid, (collage) – ca. 1968-1970, Minnesota Museum of American Art

- Morning of the Rooster

- Patchwork Quilt (collage) – 1970, Museum of Modern Art

- Pepper Jelly Lady (colour lithograph), Minnesota Museum of American Art

- Piano Lesson (painting) – Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, inspired the play The Piano Lesson

- Pittsburgh Memory (collage) – 1964, Collection of w, New York.[57] Used as anthology art for The Roots anthology ...And So You Shoot Your Cousin.

- Prevalence of Ritual: Tidings (collage)

- Recollection Pond (tapestry) – 1974–1990, vii plus ane artist'due south proof/viii made, Mount Holyoke College Fine art Museum; Port Authority of NY & NJ; York College, Metropolis University of New York; The Metropolitan Museum of Art[58]

- Render of the Prodigal Son – 1967, Albright-Knox Art Gallery

- Rocket to the Moon (collage)

- She-Ba

- Showtime (painting)

- Summertime (collage) – 1967, Saint Louis Art Museum

- The Woodshed

- Wrapping it up at the Lafayette

- The Dove 1964

- "The Family" 1941

- "The family" 1975

Selected collections [edit]

- Art Museum of Southeast Texas, Beaumont, Texas

- Art Museum of West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia

- Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Madison, WI

- Minneapolis Plant of Fine art, Minneapolis, MN

- Minnesota Museum of American Fine art, St. Paul, MN

- Museum of Modernistic Art[59]

- Whitney Museum of American Art[60]

Run across also [edit]

- African-American fine art

- List of Federal Art Projection artists

Farther reading [edit]

- Price, Sally and Richard Price. Romare Bearden: The Caribbean Dimension. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Printing. 2006. ISBN 0-8122-3948-2

References [edit]

- Notes

- ^ a b Fraser, C. Gerald. Romare Bearden, Collagist and Painter, Dies at 75. The New York Times. March 13, 1988.

- ^ a b "TIMELINE". Bearden Foundation . Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ Jose Jose - Amar y Querer, archived from the original on Dec xi, 2021, retrieved October xiii, 2019

- ^ a b c O'Meally, Robert Yard. (2019). The Romare Bearden Reader. Durham: Knuckles University Press. p. nine. ISBN9781478000440.

- ^ "National Gallery of Art: The Art of Romare Bearden - Introduction". Nga.gov. Archived from the original on Jan 23, 2016. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ West, Sandra L.. Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance. United Kingdom, Facts On File, Incorporated, 2003.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h i j one thousand l m "Bearden, Romare". Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford Academy Press. Retrieved Jan 19, 2017.

- ^ "Bearden Foundation". Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved Apr xiv, 2013.

- ^ a b Romare Bearden Foundation, 1990

- ^ "Biography". Romare Bearden Foundation. Romare Bearden Foundation. Archived from the original on January 31, 2017. Retrieved Jan 27, 2017.

- ^ Wang, Daren. "A giant gets his due". ajc . Retrieved February eleven, 2021.

- ^ a b Schwartzman, Myron; Bearden, Romare (1990). Romare Bearden. Harry Northward. Abrams. p. 58. ISBN978-0-8109-3108-4.

- ^ "Romare Bearden Made Art Editor at Higher". New York Age. February 27, 1932.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-condition (link) - ^ a b c Campbell, Mary Schmidt (Baronial eight, 2018). An American odyssey : the life and work of Romare Bearden. New York. ISBN978-0-19-062080-half-dozen. OCLC 1046634115.

- ^ Toll, Sally. (2006). Romare Bearden : the Caribbean dimension. Price, Richard, 1941-, Bearden, Romare, 1911-1988. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 18. ISBN0-8122-3948-2. OCLC 65395208.

- ^ "Romare Bearden". Smithsonian Institution . Retrieved February 11, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Parham, Jason (March 14, 2012). "The Man Who Spurned a Baseball Career to Go a Renowned Artist". The Atlantic . Retrieved February eleven, 2021.

- ^ Smee, Sebastian. "Review | Outset the New Yorker profiled Romare Bearden. Then the artist and activist decided to tell his ain story, in pictures". Washington Postal service. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f chiliad h i j chiliad l Valakos, Dorothy (1997). Bearden, Romare (Howard), St. James Guide to Black Artists. Detroit: St. James Press. pp. 41–45.

- ^ Witkovsky 1989: 258

- ^ Witkovsky 1989: 260

- ^ Witkovsky, 1989: 260

- ^ [1] Archived May 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Carter, Richard (2003). "The Fine art of Romare Bearden: A Resource for Teachers" (PDF). nga.gov.

- ^ a b Bearden, Romare & Henderson, Harry, P. (1993). A History of African-American Artists. From 1792 to present. New York: Pantheon Books. p. 400.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kroiz, Lauren. "Relocating Romare Bearden'due south Berkeley: Capturing Berkeley's Colorful Diversity". Boom California . Retrieved March 1, 2022.

- ^ "Berkeley - The Urban center and Its People". Metropolis of Berkeley website . Retrieved March i, 2022.

- ^ "City Logo". Berkeley Historical Plaque Project . Retrieved March 1, 2022.

- ^ a b Mercer, Kobena. "Romare Bearden, 1964; Collage as Kunstwollen." Cosmopolitan Modernisms. London: Establish of International Visual Arts, 2005. 124–45.

- ^ a b Armstrong, Elizabeth (2005). Villa America: American Moderns, 1900-1950. Orange Canton Museum of Art. pp. 98. ISBN0-917493-41-9.

- ^ a b "Factory Workers, Romare Howard Bearden". artsmia.org . Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Witkovsky 1989: 266

- ^ Witkovsky 1989: 267

- ^ Brenner Hinish and Moore, 2003

- ^ Fine, 2004

- ^ [2] Archived February eighteen, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Oisteanu, Valery (May 2011). "Romare Bearden (1911–1988): Collage, A Centennial Commemoration". The Brooklyn Rail.

- ^ Greene, 1971.

- ^ a b "Bearden Subway Mural Takes Pittsburgh by Surprise". ARTINFO. Apr 25, 2008. Retrieved April 28, 2008.

- ^ Ulaby, Neda. "The Art of Romare Bearden: Collages Fuse Essence of Sometime Harlem, American South", NPR. 14 September 2003.

- ^ a b Gerber, Sanet. "Return of Odysseus past Romare Bearden." Welcome to DiscountASP.NET Spider web Hosting. GerberWebWork, n.d. Web. March 3, 2012.

- ^ "Romare Bearden and Abstract Expressionist Fine art." Segmentation. SegTech., December 5, 2011. Web. March 3, 2012.

- ^ Library of Congress. Copyright Office. (1960). Catalog of Copyright Entries 1960 Dramas Jan-December 3D Ser Vol fourteen Pts iii-iv. United states of america Copyright Office. U.S. Govt. Print. Off.

- ^ Gussow, Mel (2001-05-23). "Loften Mitchell, 82, Dramatist and Writer on Blackness Theater (Published 2001)". The New York Times.

- ^ Carter, Richard, ed. (2003). "The Art of Romare Bearden: A Resource for Teachers" (PDF). National Gallery of Art.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Wynn, Ron. "Branford Marsalis Quartet: Romare Bearden Revealed". JazzTimes . Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "The Romare Bearden Foundation - Mission". Beardenfoundation.org. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved Nov 15, 2015.

- ^ "Romare Bearden Foundation – Foundation Programs". Beardenfoundation.org. Archived from the original on Oct 21, 2015. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ [3] Archived January fourteen, 2014, at the Wayback Automobile

- ^ "Bearden Park Blueprint - Support Romare Bearden Park!". Beardenfoundation.org. Retrieved November fifteen, 2015.

- ^ "Romare Bearden Park" (PDF). Mecklenburg County Park & Recreation. 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "DC Moore Gallery, Romare Bearden artist page". Dcmooregallery.com. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ Romare Bearden: A Black Odyssey, Columbia Academy Center for Educational activity and Learning, September 22, 2015

- ^ "American Artist Romare Bearden's Work Honored on Forever Stamp". About.usps.com . Retrieved Jan 20, 2020.

- ^ Calos, Katherine (Jan nineteen, 2017). "VMFA'south Bearden acquisition called a 'game-changer': Three Folk Musicians' collage will go on display in Richmond on Feb. l". Richmond Times-Dispatch. No. Metro. pp. B1, B3.

- ^ Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York. Prometheus Books. ISBN i-57392-963-eight.

- ^ "NGA: The Art of Romare Bearden - Pittsburgh Memory, 1964". Nga.gov. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved Nov 15, 2015.

- ^ "GFR Tapestry Program » Romare Bearden, "Recollection Pond"". Tapestrycenter.org. February 22, 1999. Retrieved November xv, 2015.

- ^ "MoMA".

- ^ "Whitney Museum".

- Sources

- Bearden, Romare, Jerald L. Melberg, and Albert Murray. Romare Bearden, 1970-1980: An Exhibition. Charlotte, N.C.: Mint Museum, 1980.

- Brown, Kevin. Romare Bearden: Creative person. New York: Chelsea Firm, 1994.

- East Stop/Eastward Freedom Historical Society (January 16, 2008). Pittsburgh's East Liberty Valley. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN978-ane-4396-3574-2.

- Romare Bearden; Ruth Fine; Jacqueline Francis (2011). Romare Bearden, American Modernist. National Gallery of Fine art. ISBN978-0-300-12161-two.

- Romare Bearden; Ruth Fine; Mary Lee Corlett; National Gallery of Fine art (U.Due south.) (2003). The Art of Romare Bearden . National Gallery of Art. ISBN978-0-89468-302-2.

- Greene, Carroll, Jr., Romare Bearden: The Prevalence of Ritual, Museum of Modern Art, 1971.

- Romare Bearden Foundation. "Romare Bearden Foundation Biography". Archived from the original on Nov 24, 2005. Retrieved October iv, 2005.

- Vaughn, William (2000). Encyclopedia of Artists. Oxford University Press, Inc. ISBN0-19-521572-nine.

- Witkovsky, Matthew Southward. 1989. "Experience vs. Theory: Romare Bearden and Abstruse Expressionism". Black American Literature Forum, Vol. 23, No. ii, Fiction Effect pp. 257–282.

- Yenser, Thomas, ed. (1932). Who's Who in Colored America: A Biographical Lexicon of Notable Living Persons of African Descent in America (Third ed.). Who's Who in Colored America, Brooklyn, New York. [Provides biography of mother, Bessye J. Bearden]

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Romare Bearden at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Romare Bearden at Wikimedia Commons - The Romare Bearden Foundation website

- The Fine art of Romare Bearden at the National Gallery of Art, Washington

- Chicago Tribune: A deeper look at an artist who refused to exist white

- Marshall Arts presents Romare Bearden

- Bearden Foundation biography

- Romare Bearden Images: Hollis Taggart Galleries

- "Romare Bearden: The Music in His Art, A Pictorial Odyssey" – by Ronald David Jackson, video, 2005

- Romare Bearden Artwork Examples on AskART.

- A finding aid to the Romare Bearden papers, 1937-1982, in the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

- Columbus Museum of Art Bearden's 1967 collage and mixed media piece La Primavera (click on moving-picture show for larger image)

- Conjuring Bearden Exhibit at the Nasher Museum of Fine art

- Romare Bearden's public artwork at Westchester Square-East Tremont Avenue, commissioned past MTA Arts for Transit.

- The Bearden Project from the Studio Museum Harlem

- Romare Bearden "The Storyteller," Fine art and Antiques, October 2012

- Romare Bearden, "A Griot for a Global Hamlet", The New York Times, 2011

- Romare Bearden, "The Fine art of Romare Bearden Opens at the High Museum," ArtDaily, Oct 2012

- "Romare Bearden: A Black Odyssey," Columbia University Heart for Didactics and Learning, September 22, 2015

- Romare Bearden at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, MN

pasleymonexte1974.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romare_Bearden